Binoculars can provide a completely different and invigorating experience while on your travels

Do you know anyone who travels simply to move around the planet? I certainly don’t. The whole point of traveling is to experience things along the way. And whether your passion is to experience scenery, history, geology, astronomy, wildlife—or, as in my case, every one of these—your travels can be inestimably enriched if you carry binoculars.

What could be more magic than an invention that brings the world seven, eight, even ten times closer? A distant, snow-capped peak, an inaccessible cliff dwelling across a canyon, a shy bird, a dangerous animal, the moons of Jupiter: a thousand things can be enjoyed, evaluated—or avoided—with binoculars.

I’ve used binoculars for fun, as well as professionally—as a sea kayaking, birding, and safari guide—so I’ve learned a fair bit about evaluating them. Like many products, to a large extent you get what you pay for—but there are ways to ensure you get the best instrument for your needs regardless of how much you plan to spend.

The most visible component of a binocular (technically the correct term, not “a pair of binoculars”) is the front, objective lens. All other aspects of construction being equal, the diameter of this lens determines, 1) how much light the binocular gathers and how bright the image appears, 2) how much magnification the binocular can effectively deliver, 3) how bulky and heavy the binocular will be to carry and use, and 4) how much it will cost. Small—e.g., 20 or 25mm—objectives equal low light-gathering, low power, light weight, and lower cost. Larger—30 to 60mm—objectives gather more light, allow higher magnification, are heavier and bulkier, and cost more.

Binoculars are referred to by their magnification factor (the number of times they make an object appear closer) followed by the objective diameter—6×20, 8×42, 10×50, etc. The compromise between objective-lens size and magnification is one of the important decisions you’ll need to make when selecting a binocular. So, let’s look at the relationship.

Hold a binocular a foot or so from your face while it’s pointed at something bright. The little circle of light in the eyepiece is called the exit pupil. The diameter of that exit pupil is a function of the objective lens diameter divided by the magnification. A 10×40 binocular has a 4mm exit pupil; so does an 8×32 binocular. An 8×40 binocular has a 5mm exit pupil, in a compact 8×20 binocular it is 2.5mm.

This measurement is critical because of the variable diameter of your own pupils. In bright sunlight they contract to around 2mm, but near dark they expand to 4, 5, or 6mm, depending on your age (as we age our pupils cannot expand as much). Consider the 2.5mm exit pupil of the compact 8×20 binocular. Looking through it in bright sunlight, with your own pupils constricted to 2mm or so, you’ll see a full view. But near dusk, when your pupils have expanded, you’ll see dark clouding around the central image, because your pupils are larger than the exit pupil. This vignetting means that binoculars with small exit pupils don’t perform well in low light.

So, all else being equal, a larger exit pupil equals better low-light viewing. However, magnification also has an effect. Note the 10×40 and 8×32 binoculars I listed above. Despite identical 4mm exit pupils, the 10×40 will perform better at dusk due to the greater magnification. (As we’ll see, many other factors also contribute to brightness.)

Herewith my first guideline: For all-around use I do not recommend a binocular with an exit pupil smaller than 4mm.

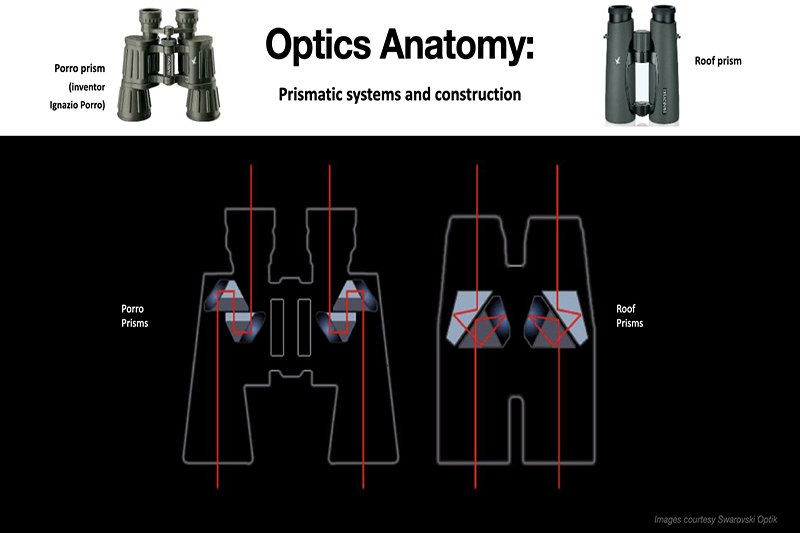

The next critical design component of a binocular are the prisms, which are incorporated for two reasons: first, to correct the image orientation, which as it comes through the objective lens is turned upside down and reversed; second, to allow the binocular to be shorter than it otherwise would be to gain sufficient magnification.

You’ve seen dispersive prisms—the triangular versions that break up white light into its constituent colors. Binoculars employ reflective prisms, which at their most basic work on the principle of internal reflection—light entering perpendicular to one surface is reflected off the angled surface behind it. As long as the light hits the back surface at what’s called a critical angle, no mirrored surface is needed; perfect reflection is achieved at the glass/air interface. You can see this effect by looking up at the surface of an aquarium at an angle that turns it into a mirror.

Binoculars employ one of two types of prism. Porro prism instruments display the classic offset configuration, with objective lenses set outboard of the eyepieces (or, in some compact binoculars, inboard). Porro prisms obtain perfect internal reflection using nothing but glass. This can give them slightly better light transmission and clarity than roof prisms (see below). Additionally, porro-prism binoculars with wide-set objective lenses produce a fractionally better three-dimensional view. Disadvantages include poor close focusing ability (an artifact of the wide-set objectives) and greater weight and bulk.

Roof prisms overcome those weight and bulk issues, because incoming light rays are “bounced” more times in a tighter space than in a porro-prism instrument. Note in the diagram how the incoming and outgoing rays are in line; thus roof-prism binoculars can be configured as straight tubes, saving the weight as well as the bulk of the offset tubes.

However, the internal alignment (collimation) of roof prisms is more difficult to replicate consistently and durably. Also, a roof prism requires a reflective coating (either silver or, much better, dialectric) on one surface, plus phase-correction coatings to reduce light polarization—neither of which is an issue with porro prisms. Nevertheless, due to their compactness, light weight, and handling ease (they are much easier to use one-handed), virtually all premium and ultra-premium binoculars are roof-prism instruments.

The very best prism glass is called BaK4, for BaritleichKron or Barium Crown, made by Schott AG. Many cheap binoculars claim to employ this glass when in fact they do not. The manufacturer’s reputation—and price—is nearly the only way to be sure you’re getting Schott BaK4. And even given that, manufacturing tolerances, coatings, and a dozen other parameters will make or fail to make a high-performing prism.

Now: Look at the lenses of your binoculars and you’ll notice a definite tint—purplish in some binoculars, greenish in others, reddish in others. Why?

All glass reflects some light—look at a piece of window glass and you’ll see this. Furthermore, there is a reflection both when the light enters the sheet of glass—or a lens—and when it exits the back of it, reducing the amount of light making it all the way through by ten percent or more. Multiply that by the several lenses in a binocular and the light fall-off is severe. Just before WWII Zeiss introduced anti-reflection coatings, which increased light transmission through binoculars from 50-60 percent to 70-80 percent. Today’s high-end binoculars are fully multi-coated—every glass surface has an anti-reflection coating comprising up to seven layers—and total light transmission is well over 90 percent. However, like BaK4 prisms, “fully multi-coated” can mean a lot or not much at all. Simply put, a $100 Chinese binocular with “fully multi-coated optics and BaK4 prisms” will not have the same stuff inside as a $2,000 binocular with “fully multi-coated optics and BaK4 prisms.”

Back to the objective lenses. Different colors of the spectrum bend at slightly different angles when passing through a lens, and if they are not brought together by the time they reach the eyepiece, objects will display a slight fringe of spurious color—usually blue, because blue light is more sharply diffracted then yellow or red. This chromatic aberration can be controlled using achromatic objective lenses, which alter the diffracting characteristics of the lens—generally by combining two types of glass with different refractive qualities—and/or with aspheric lenses, and/or with extra-low-dispersion (ED) glass. As with everything we’ve discussed, this adds to the cost of the binocular as well as the quality of the image.

There’s more: weather sealing and nitrogen-purging, internal baffling, hydrophobic lens coatings, reinforced prism housings. Chassis construction: plastic, composite, aluminum, or magnesium?

So, you’re now loaded down with technical information. You could simply make a checklist of all these features and order a binocular online. But nothing—nothing—substitutes for handling the instrument and looking through it. If at all possible, you should shop in person, at a store that will let you spend time with different models.

First, decide on the right size for your needs. For all-around use while saving weight, bulk, and cost, an 8 x 30 or 8 x 32 binocular is ideal. If you’re a hunter or birder (or both, like me), you might step up to an 8 x 42 or 10 x 42. I don’t recommend magnification greater than 10 for a hand-held binocular—and by all means avoid zooms.

Does the one you are trying feel balanced? Does the focus knob fall easily to a forefinger, or do the strap hangers intrude? If you wear glasses, do the eyecups screw down far enough to produce a full field of view? Fifteen millimeters of eye relief is minimum for use with glasses; eighteen or twenty is better.

Now comes the critical part. You need to look through that instrument for as long as you can without looking away. A minute or two is minimum; five minutes is better. Check for sharpness (especially at the edges of the field of view), and color fringing. Do you feel any eye strain at all while looking around? If you do, reject that model and try another. When you take your eyes away from the instrument, do you consciously have to “realign” them? Reject.

What about brands? Choose any European-built model from the Big Three—Swarovski, Zeiss, or Leica—and you’ll have a tool for life offering unsurpassed brilliance and durability. The view through my Swarovski Pure 10 x 42, for example, is simply breathtaking, and fully justifies its premium entry fee. In mid-priced binoculars I like the Vortex Viper HD, Nikon Monarch M5, and the Opticron Imagic. If you’re on a very tight budget, look at the Nikon Prostaff.

The best binoculars available today offer brilliant, sharp, true-color views comfortable for hours of viewing without eye strain; complete weather sealing; shock-proof construction; light weight, and a lifetime guarantee—often transferable. A premium binocular represents a considerable investment that will repay itself every time you use it, and continue to do so for as long as you continue to explore our planet and its landscapes, history, wildlife . . .

OutdoorX4 Magazine – Promoting responsible vehicle-based adventure travel and outdoors adventure