Paper maps and waypoints can be invaluable navigation resources while traveling overland

In April 2008, Four Wheeler magazine published an article titled “101 Places to Wheel Before You Die – Global.” Two things struck me about the article: First, many of the places mentioned I would consider overlanding destinations rather than “wheeling” opportunities. Second, the list included Camp Six road in Belize, a route I had already attempted and knew a lot about. Apart from the mud and jungle, one thing stuck out in my memory: the challenge we had finding the road in the first place. Curious, I took the waypoint given in the Four Wheeler article and compared it with my own.

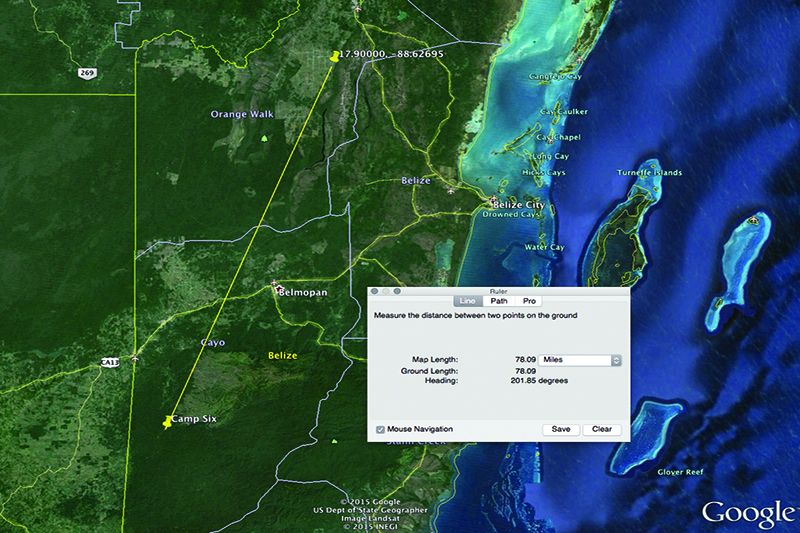

Four Wheeler waypoint is a long way from the real junction to Camp Six road

The two were not even close—and from that grew an excellent lesson in navigation.

Here is the information from Four Wheeler:

Camp Six Road, near San Ignacio, Belize.

Location: Approximately 20 miles south of San Ignacio, at approximate GPS waypoints 1754.000N, 8837.617W.

Note those final numbers: 1754.000N, 8837.617W. While clearly some sort of coordinate, if you plug them, as is, into Google Earth you’ll get an error message: “Not found.” In other words, the waypoint is not really a waypoint, and the reason has to do with two concepts we always need to keep in mind when describing coordinates: Units and formatting. Look at these numbers long enough, and it becomes pretty obvious that the units are missing. A quick change to 17°54.000’N, 88°37.617’W and we are getting somewhere, a position in Belize at the very least. Even so, the formatting is not good. A waypoint describes a singular position on the planet, and should be completely unambiguous (more on this a little later). In most cases it isn’t critical, but in an emergency, or when giving directions or locations to people getting to remote locations, small mistakes can be dangerous and, at worst, deadly. So let’s review the basics.

On the ground it can be obvious why a waypoint is needed: The junction is just behind the trucks

For latitude and longitude, there are three basic formats. The first is degrees, minutes, seconds (abbreviated DMS), and is the age-old format used by pirates and the great explorers of the Age of Discovery. A DMS waypoint takes the form N17°54’00”, W88°37’37”. The units are ° for degrees, ’ for minutes and ” for seconds. (A minute is 1/60th of a degree; a second is 1/60th of a minute.) Sometimes the seconds are in decimal notation going down to the tenths or hundredths of seconds, for example W88°37’37.02”. N signifies the northern hemisphere and W signifies west of the Prime Meridian, which can also be denoted as -E. (In Europe W is usually –E, and technically this is the more correct way of doing it. It seems we just don’t like dealing with negative numbers in North America.) The second format is degrees decimal minutes, abbreviated DMM. In this case we are converting seconds to decimal minutes by dividing the seconds by 60. In the case of longitude, in the example 37.02 seconds divided by 60 gives 0.617 minutes. The waypoint in question was mostly in DMM format: N17°54.000’, E88°37.617’.

The final format is decimal degrees or DDD, which is the easiest format to use when working with computers, as both latitude and longitude can each be represented with a single number. Here, decimal minutes are divided by 60 and added to the degrees, giving us N17.90000°, W88.62695°. To make DDD computer friendly and get rid of any text complications, we turn the waypoint into 17.90000, -88.62695 and do away with the units (after I was just harping on how important they are!). Here, negative for latitude is south and negative for longitude is west, which takes the place of the cardinal directions. Not ideal, but so long as we understand the conventions, we can all understand what is going on. Note that all the waypoints given above are the same position (Camp Six, we think), just in different formats.

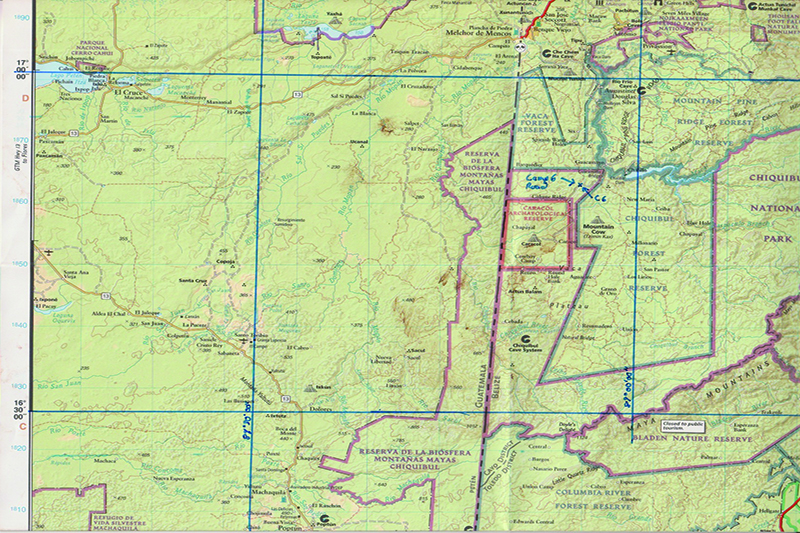

First steps: Find the point of interest on the map and draw in the lines of latitude and longitude

So that’s latitude and longitude, two-thirds of the basic coordinate system for any position on the face of the earth. Now, before we continue with the coordinates and using them, there is just a little more info I’d like to get out of the way. When I said that a waypoint needs to be unambiguous, that was true, but as many of you already know, it isn’t as simple as it seems. So we are going to make a short foray into datums (not data) and projections to clear up these often-confused terms.

The Earth is not a perfect ball, it’s what is called an ellipsoid—a slightly flattened sphere longer around the equator than around the prime meridian. In order to account for this imperfect shape, we use something called a datum, a mathematical construct to simulate the actual shape of the planet, or at least the part of the planet we are interested in mapping. There are many datums, some regional and some global, and changing the datum on a waypoint can lead to a difference in up to tens of kilometers on the ground; easily enough to miss a junction or a campsite. The version of Garmin Basecamp I am running on my computer has 129 different datums available for use, with names from Ain El Abd 1970 to Zanderij. Lucky for us there is one datum that has become almost universal: World Geodetic System 1984 (WGS84), as this is what the GPS system uses and most GPS software and hardware are defaulted to. As long as your map (either paper or electronic) and your GPS are set to the same datum, you can mostly forget that datums are involved. But keep an eye on what your maps are using, as a lot of US maps use NAD27 or NAD83 and the difference between, for example, NAD27 and WGS84 is around 60 meters on the ground.

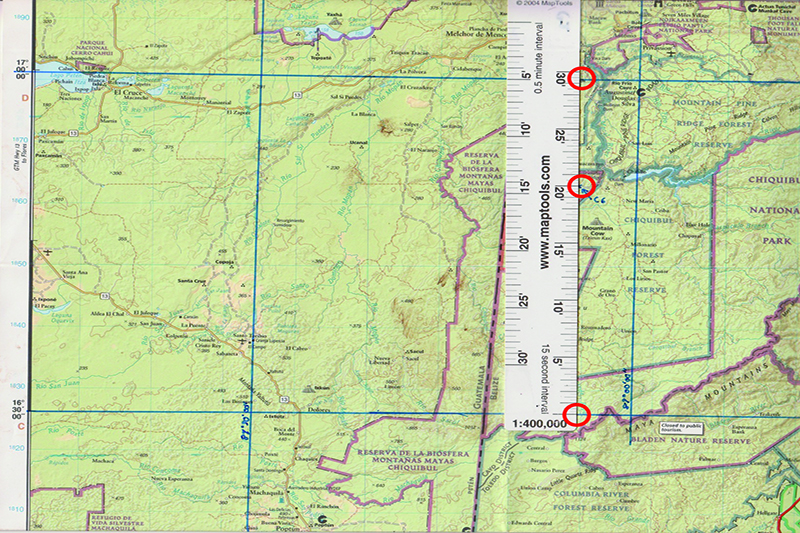

Latitude is easiest to measure, as the ruler lies vertical on the map. (Note, the upper mark on the ruler should match the 17° line of latitude; it does not due to poor line drawing)

That brings us to projections. The Earth is an ellipsoid, and maps are planes. If you imagine peeling an orange and then spreading the peel flat, that is how projections work: projecting a curved surface on to a flat surface. No map projection works for the entire planet, and some distort the continents more than others. Looking at the size of Alaska on a globe versus on a standard world map will illustrate the distortion that projections can impart. Typically for navigation purposes we will use maps of fairly small areas, and in most cases these will use the transverse Mercator projection, which imparts low variation in scale over small areas. In most cases we don’t really need to worry about projections unless we are calibrating a map image in a mapping program like Ozi Explorer or MacGPS Pro and there, just like with datums, we have to make sure our projections are the same in the software and on the map.

Now let’s get back to Camp Six road in Belize. We have a waypoint from the Four Wheeler article in three formats that are useable. We will assume that the waypoint is using the WGS84 datum, because none is mentioned. If we plug any of those into Google Earth, we get a position in Belize northwest of Belize City in the Orange Walk District. That seems like a great start, but unfortunately if you went to that location with the intent of doing Camp Six road, you would be very disappointed. You would find yourself in farmland some 78 miles northeast of the start of Camp Six, practically in the opposite direction from their description of “20 miles south of San Ignacio.” What went wrong?

The easiest way to find out is to locate Camp Six road independently. Luckily National Geographic produces an excellent Belize map in their Adventure Map series, and the Camp Six road is marked on it. The “start” of Camp Six road in this case is the intersection of Camp Six and the Chiquibul Pine Ridge Road. Back when I first did Camp Six I did not have a digital version of the National Geographic Map as I do now, and it was before Four Wheeler suggested the road. This was on a No Limit Expeditions reconnaissance trip, and our only reference to Camp Six was the National Geographic map. To find it required taking a waypoint off the map so we could plug it into the GPS. Before you say, “Why not just drive down the Pine Ridge road to the junction?” you have to understand that in dense broad-leaf forest like the Chiquibul, tracks get so completely overgrown they are impossible to see, even when you are standing right in front of them. This makes having a waypoint invaluable. So, how do we get a waypoint off a paper map?

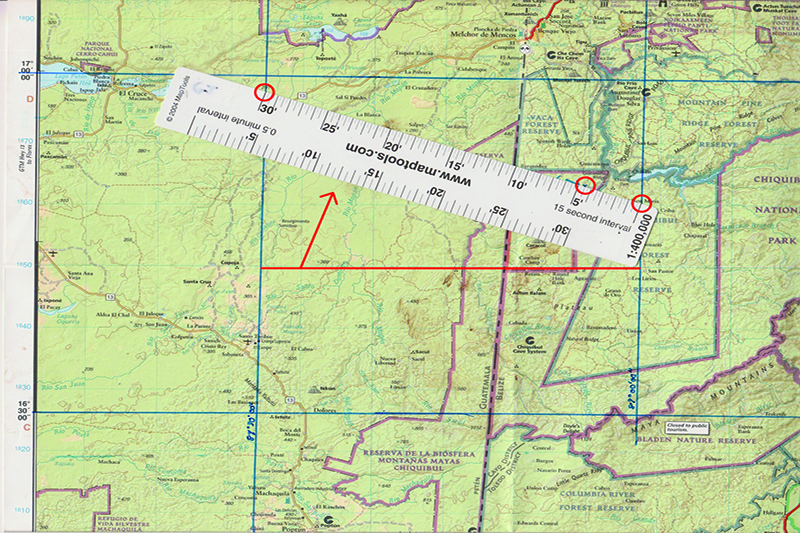

For longitude, rotate the ruler so the marks match the lines of longitude and line up with the point of interest. Measure from right to left.

First we need some tools: A good map ruler, pens, and a calculator can be helpful. The ruler can be a regular ruler or a designated map ruler like one from MapTools.com. I use their excellent Explorer Set which includes 24 map rulers at common scales from 1:24,000 to 1:500,000 and covers all the scales found on the Delorme Atlas & Gazetteer state topo series. Since the Belize map is at 1:400,000 scale, we will use the 1:400,000 map ruler. Also note that the National Geographic map is using the NAD27 datum.

First, find the point of interest on the map (for the following example, refer to the accompanying pictures). It will often help to draw in the lines of latitude and longitude from the edges of the map around the point of interest so they can be easily seen. Latitude is the easiest measurement to take, so we start there. Since lines of latitude are parallel, they are always the same distance apart, and the scale can be placed vertically with the lower mark on the line of latitude below the point of interest, running up through the point of interest. We then count the degrees and seconds from the line of latitude to the point of interest and add that to the value on the line of latitude we are measuring from. In this case the Camp Six junction is between N16°30’00” and N17°00’00”. Using the map ruler we find that the junction is 20’3” north of the N16°30’ parallel, so the latitude will be N16°30” + 20’3” = N16°50’03”.

A combination of paper and GPS can be a very powerful tool while exploring.

Longitude is a bit more complicated since the lines are not parallel and the direction of increase in the Americas is from right to left. If you place the ruler horizontally on the map, the scale does not match the lines of longitude except on the equator. We correct this by rotating the ruler until the lines of longitude match the ruler and the ruler passes through the point of interest (shown in the pictures). The Camp Six road junction lies between W89°00’00” and W89°30’00”. Lining up the ruler we can see it is 4’30” west of the 89° line so W89°00’00” + 4’30” = W89°04’30”. And now we have a complete waypoint: N16°50’03”, W89°04’30”. Converting to DMM we get N16°50.05’, W89°04.5’ and DDD we get N16.834°, W89.075°. In computer-friendly DDD this would be 16.834, -89.075. Since the map used the NAD27 datum, this waypoint is also NAD27. Converting datums can be a bit of a mathematical exercise, but luckily we have an easy way to do it in the next step. Before we plug the waypoint into the GPS, set the GPS to the NAD27 datum, and then enter the waypoint into the GPS and set the GPS back to WGS84. The GPS does all the datum conversion work for us and we now have a waypoint in WGS84: N16°50’05.94”, W89°04’29.94” in DMS, N16°50.099’, W89°04.499’ in DMM and N16.8349°, W89.0749° in DDD.

This waypoint is on the Chiquibul Pine Ridge Road, so that is a step in the right direction. The final test, of course, is to go to Belize and see if the waypoint is correct, and when I did that I found that the entrance to the Camp Six road was just 22 meters away from the waypoint taken off the map. Not bad for a map at 1:400,000 scale and certainly the only way we could have found the road so quickly.

Any way you cut it, though, it isn’t close to the waypoint given by Four Wheeler. To their credit they did put the word “approximate” twice in their location description, but the lesson here is to always verify any navigation information you get if at all possible, and take things given in print with a grain of salt.

Editor Note: This article first published in Issue 13 of OutdoorX4 Magazine. You can view that issue HERE.

OutdoorX4 Magazine – Promoting responsible vehicle-based adventure travel and outdoors adventure